Managing Cryptographic Keys

which are used to Encrypt and Decrypt Personal Data

BYOK

(Bring Your Own Key)

Control Your Own Key

Hold Your Own Key

CYOK

HYOK

The Jurisdictional and Cryptographic Determinants of Data Processor Status

The architecture of modern Software as a Service (SaaS) platforms has introduced a fundamental shift in the nature of data custody and legal accountability. In a standard B2B deployment model, the SaaS provider often assumes the role of an orchestrator, managing a third-party cloud infrastructure on behalf of its customers. Within this paradigm, the implementation of robust encryption protocols—scrambling data at rest and in transit—is frequently touted as a mechanism that isolates the provider from the underlying content of the data. However, a significant legal controversy persists: when a SaaS provider manages the cloud environment and retains access to encryption keys, even if those keys are never utilized and the data is never decrypted, does that provider remain a "Data Processor" under global privacy regulations? The answer to this question involves a complex synthesis of technological realities and evolving legal frameworks, ranging from the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to the United States' sectoral regimes and the emerging federal laws in the Middle East and Latin America.

The classification of an entity as a data processor is not merely a technical label but a functional legal determination that triggers a suite of mandatory obligations, primarily the execution of a Data Processing Addendum (DPA). As organizations increasingly prioritize data sovereignty and cryptographic isolation, understanding the thresholds for processor status across different jurisdictions is essential for risk management and regulatory compliance. The following analysis explores the legal definitions of "processing," the implications of key management in the context of "personal data," and the specific requirements for DPAs under a wide range of geographical and federal regulations.

A Comprehensive Analysis of SaaS B2B Deployments and Key Management

Foundations of the Data Processor Classification

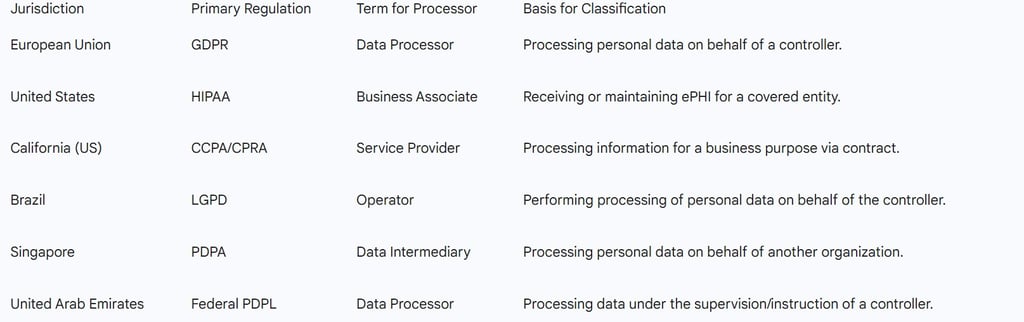

The threshold for being classified as a data processor begins with the definition of "processing." Across almost every modern privacy framework, the term is defined with extreme breadth. In the context of SaaS, the provider is typically the entity that provides the infrastructure, storage, and processing capabilities that make the collection and utility of data possible for the customer, who acts as the data controller. The controller determines the "why" and "how" of the data usage, while the processor executes these instructions through its platform.

Under the GDPR, Article 4 defines processing as any operation or set of operations performed on personal data, including collection, recording, organization, structuring, storage, and even the mere "holding" of data.1 If a SaaS provider hosts encrypted data on its managed cloud servers, it is unequivocally "storing" and "holding" that data. The fact that the data is unintelligible to the provider due to encryption does not negate the fact that the provider is performing a storage function on behalf of the controller. Consequently, the provider is almost always categorized as a processor.

Table 1: Regulatory Frameworks and Processor Terminology

Implications Under the GDPR and UK GDPR

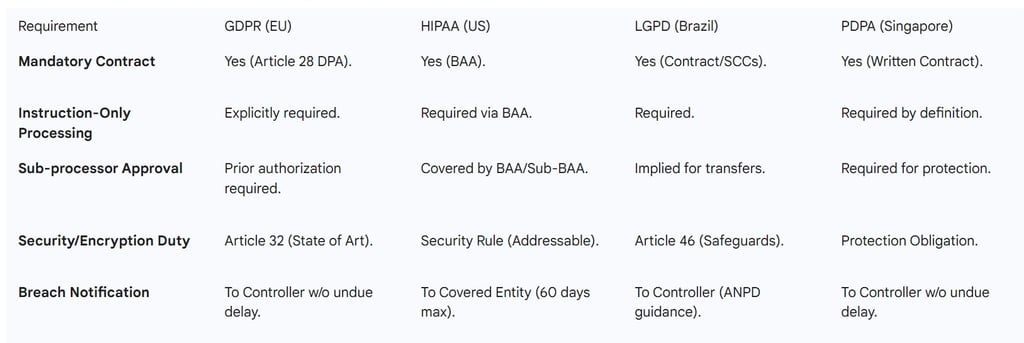

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) sets the global benchmark for the controller-processor relationship. Article 28 of the GDPR explicitly mandates that any processing carried out by a processor on behalf of a controller must be governed by a contract or other legal act. This contract, commonly referred to as a Data Processing Addendum (DPA), is not optional; it is a mandatory requirement for compliance.

The Threshold of "Personal Data" and Encryption

A common argument used by SaaS providers is that encrypted data, for which they do not use the keys, should not be considered "personal data" in their possession. However, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) and the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) have provided guidance that challenges this view. Encrypted data is essentially a form of pseudonymization because the data can still be attributed to a specific natural person with the use of additional information—the decryption key.

If the SaaS provider holds the keys, even if they are stored in a secure vault like an HSM (Hardware Security Module), the provider is considered to have access to that "additional information". Therefore, the data remains personal data in the hands of the provider. The ICO clarifies that while encryption is an essential security measure under Article 32, it does not exempt the processor from the requirements of Article 28. The provider is still "holding" the data, which is a processing activity, and because they could decrypt it, they are processing personal data.

The Necessity of the DPA

Operating without a compliant DPA creates immediate regulatory liability for both the SaaS provider and the customer. Under Article 28, a controller is legally obligated to only engage processors that provide "sufficient guarantees" to implement appropriate technical and organizational measures. For the SaaS provider, the DPA serves several critical functions:

Instructional Boundaries: It documents that the provider will only process data according to the controller's instructions, preventing the provider from being reclassified as a controller (which carries much higher liability).

Liability Allocation: It establishes who is responsible in the event of a breach. For example, if a vulnerability in the provider’s managed cloud infrastructure leads to a leak, the DPA determines the notification obligations and indemnity limits.

Sub-processor Transparency: Since the SaaS provider is managing a third-party cloud (e.g., AWS, Azure), those cloud providers are "sub-processors." The GDPR requires the SaaS provider to have a DPA with the cloud provider and to disclose these sub-processors to the customer.

The ICO’s updated guidance on encryption emphasizes that encryption should be used alongside other controls such as access restrictions and secure key management. The DPA is the legal vehicle that verifies these security measures are in place, fulfilling the "accountability" principle of the GDPR.

The United States: HIPAA and Business Associate Status

In the United States, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) provides some of the most explicit guidance regarding the status of cloud and SaaS providers who handle encrypted data. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has addressed the specific scenario of "no-view" services.

The "No-View" Service Guidance

Under HIPAA, a "Business Associate" (BA) is any entity that creates, receives, maintains, or transmits electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI) on behalf of a "Covered Entity" (e.g., a hospital or insurer). OCR has stated clearly that a cloud service provider (CSP) that maintains encrypted ePHI on behalf of a covered entity is a Business Associate, even if the CSP does not have the decryption key and therefore cannot view the information.

The rationale provided by HHS is that while encryption protects the confidentiality of the data, it does not inherently guarantee its integrity or availability. A SaaS provider managing a cloud environment is responsible for ensuring that the encrypted files are not corrupted by malware and that they remain available during a disaster (contingency planning). These responsibilities are core requirements of the HIPAA Security Rule.

The Mandatory Business Associate Agreement (BAA)

Because the SaaS provider is a Business Associate, they must enter into a Business Associate Agreement (BAA) with the customer. The BAA is the HIPAA equivalent of a DPA and must include provisions that:

Limit the BA's use and disclosure of ePHI.

Require the BA to implement administrative, physical, and technical safeguards (including encryption).

Obligate the BA to report breaches of "unsecured" PHI to the covered entity.

In the specific case where the SaaS provider does hold the encryption keys (even if not used), they have even greater responsibilities. If a breach occurs and the keys are also compromised, the incident is a "notifiable breach" because the data is no longer considered "unreadable, undecipherable, and unusable" to the unauthorized party. If the provider does not hold the keys, they may fall under a "safe harbor" for breach notification if the encrypted data is lost, but they still require a BAA for the "maintenance" of the data.

California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and CPRA

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), introduces a different set of definitions but reaches a similar conclusion regarding the necessity of contracts. The CCPA applies to "for-profit" businesses that collect the personal information of California residents and meet certain revenue or data volume thresholds.

Service Provider vs. Third Party

Under the CCPA, a "Service Provider" is a person or entity that processes personal information on behalf of a business and to which the business discloses a consumer’s personal information for a "business purpose" pursuant to a written contract. If a SaaS provider manages a cloud and hosts California residents' data, they are acting as a service provider.

The CCPA does not explicitly state that encryption changes the status of an entity from a service provider to something else. However, it does provide a critical incentive for encryption. Section 1798.150 allows consumers to institute a civil action if their "nonencrypted and nonredacted personal information" is subject to unauthorized access as a result of a business's failure to maintain "reasonable" security.

The Role of Encryption Keys under CCPA

The CCPA guidance suggests that for encryption to be "reasonable," the keys must be managed securely and separately from the data. If a SaaS provider holds the keys in the same cloud environment as the data, an auditor may determine that the security was not "reasonable," thereby exposing both the provider and the customer to statutory damages ($100 to $750 per consumer, per incident).

While the CCPA does not explicitly use the term "DPA," the required contract between a business and a service provider must include specific language that:

Prohibits the service provider from selling or sharing personal information.

Prohibits the service provider from retaining, using, or disclosing the information for any purpose other than those specified in the contract.

Requires the service provider to notify the business if it can no longer meet its CCPA obligations.

In practice, most B2B SaaS providers combine these CCPA requirements with GDPR requirements into a single Global Data Processing Addendum.

Brazil’s LGPD and the Role of the Operator

Brazil’s General Data Protection Law (LGPD), which came into force in 2020, is heavily modeled after the GDPR. It defines the "Operator" (the equivalent of a processor) as a natural person or legal entity that performs the processing of personal data on behalf of the "Controller".

Extraterritoriality and Encryption

The LGPD has broad extraterritorial reach. It applies if the processing is carried out in Brazil, if the purpose is to offer goods or services to individuals in Brazil, or if the data was collected in Brazil. For a global SaaS provider, this means that even if their servers are located in the US or Europe, if they are managing the data of Brazilian residents, they must comply with the LGPD.

The LGPD recognizes encryption as a key security measure. Article 46 requires that controllers and operators implement technical and organizational measures to protect personal data from unauthorized access. However, like the GDPR, the LGPD treats encrypted data as personal data unless it has been "anonymized" using means that are irreversible. If a SaaS provider holds the decryption keys, the data is merely "blocked" or "pseudonymized," and the provider remains an operator.

Contractual Mandates Under LGPD

The LGPD requires that the relationship between the controller and operator be clearly defined. While the law is less prescriptive than the GDPR regarding the exact clauses of a DPA, it emphasizes that the operator must:

Perform processing according to the controller's instructions.

Maintain a record of processing activities.

Notify the controller of security incidents.

In August 2024, the Brazilian National Data Protection Authority (ANPD) introduced new rules for international data transfers, mandating the use of Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). For a SaaS provider managing a third-party cloud, these SCCs must be integrated into the DPA to ensure that the transfer of data from Brazil to the cloud provider (as a sub-processor) is legally valid.

Table 2: Comparison of Processor Obligations and Contractual Requirements

Singapore: Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA)

Singapore’s PDPA classifies processors as "Data Intermediaries" (DIs). A DI is an organization that processes personal data on behalf of another organization pursuant to a written contract.

The Protection and Retention Obligations

Under the PDPA, Data Intermediaries are exempt from most data protection obligations (like consent and access), but they are directly subject to two critical obligations:

The Protection Obligation: The DI must make "reasonable security arrangements" to protect the personal data in its possession or control.

The Retention Limitation Obligation: The DI must cease to retain personal data when the purpose for which it was collected is no longer served.

The Singapore PDPC has explicitly stated that an organization is responsible for the activities of the data intermediaries it engages. If a SaaS provider manages a cloud and holds keys, they have the data under their "control" in an electronic medium. The PDPC recommends encryption for sensitive data as part of the Protection Obligation.

The DPA in Singaporean Law

The PDPA specifically requires organizations to enter into written agreements with their data intermediaries. The PDPC has issued a "Guide on Data Protection Clauses" which provides samples for these contracts. For a B2B SaaS provider, having a DPA is the only way to demonstrate that the customer has delegated the "Protection Obligation" to the provider and that the provider has committed to meeting those standards. If a breach occurs at the cloud level (the sub-processor), the DI is responsible for notifying the customer (the controller) "without undue delay".

United Arab Emirates: Federal and Free Zone Regulations

The UAE presents a unique regulatory landscape where federal law operates alongside specialized regimes in financial free zones like the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) and the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM).

Federal Decree-Law No. 45 of 2021 (PDPL)

The UAE’s Federal PDPL, which came into effect in 2022, is heavily influenced by the GDPR. It defines the processor as any establishment or natural person that processes personal data on behalf of the controller and under its supervision.

The law applies to any processor located in the UAE, regardless of where the data subjects are, and to any processor outside the UAE that processes data of individuals residing in the UAE. Like other modern laws, it prohibits processing without consent unless an exception applies, and it mandates that controllers and processors implement "appropriate technical and organizational measures".

While the Executive Regulations for the federal law are still being finalized, the statute already requires that data processing be carried out in a secure manner. For a SaaS provider managing encrypted data and holding keys, the federal law's requirements for "confidentiality and privacy" effectively necessitate a DPA to document the provider’s role and security commitments.

DIFC and ADGM: Specialized Regimes

The DIFC (Law No. 5 of 2020) and ADGM (Data Protection Regulations 2021) have established regimes that are recognized as having "adequacy" with the GDPR.

DIFC: The Commissioner of Data Protection oversees compliance. Controllers and processors must register and pay annual fees. Breach notification must occur "without undue delay".

ADGM: The Office of Data Protection (ODP) mandates a 72-hour notification window for breaches. Fines for non-compliance in ADGM can reach up to $28 million USD.

In both free zones, the requirement for a DPA (or a written contract) between a controller and processor is explicit and mirrors GDPR Article 28. If a SaaS provider establishes a "stable arrangement" in the DIFC or processes data within the ADGM jurisdiction, they must have a DPA that includes standard privacy principles: purpose specification, data minimization, and safety/security.

Technical Architectures and Legal Control

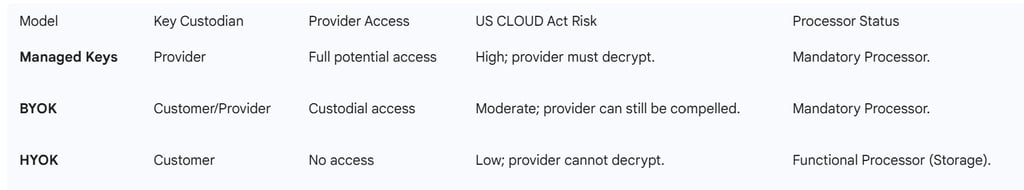

The legal classification of a SaaS provider often depends on the specific "Key Management Model" they employ. From a technical and legal standpoint, these models represent a spectrum of control and liability.

Provider-Managed Keys (High Liability)

In this model, the SaaS provider manages the encryption keys within their own cloud service account (e.g., using AWS KMS with provider-owned keys).

Technical Reality: The provider has the keys, the data, and the software. They can decrypt at will.

Legal Status: Clear-cut Data Processor. A DPA is absolutely mandatory. The provider is fully responsible for key lifecycle management (generation, rotation, destruction).

Government Access: The provider can be served with a warrant or subpoena (e.g., under the US CLOUD Act) to decrypt the data.

Bring Your Own Key (BYOK) (Moderate Liability)

In the BYOK model, the customer generates the keys and "uploads" or "links" them to the SaaS provider's cloud KMS.

Technical Reality: The customer owns the key, but the provider has "custody" of the key while it is in their KMS. The provider’s infrastructure still performs the cryptographic operations.

Legal Status: Still a Data Processor. Most regulators (including the EDPB and OCR) view BYOK as a security feature, not a jurisdictional escape. The provider still "maintains" the data and the keys.

Government Access: Because the provider has technical custody of the key in their KMS, they can still be compelled to use it to decrypt data for law enforcement.

Hold Your Own Key (HYOK) / Zero-Knowledge (Lowest Liability)

In the HYOK or "Zero-Knowledge" architecture, the keys never leave the customer’s environment (or a separate, customer-controlled vault).

Technical Reality: The SaaS provider only ever receives ciphertext. They have no way to decrypt it.

Legal Status: Technically still a Data Processor because they are "storing" personal data (the ciphertext). However, the risk profile is significantly lower. The DPA is still required to manage sub-processor liability and availability, but the "confidentiality" risk is largely transferred back to the customer.

Government Access: The provider cannot comply with a decryption order because they lack the technical capability. Law enforcement must go directly to the customer to get the keys.

Table 3: Key Management Models and Legal Implications

The Impact of the US Cloud Act and International Data Sovereignty

A critical federal regulation that influences the necessity of a DPA is the US CLOUD Act (Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act). Enacted in 2018, this law clarifies that US-based service providers must comply with warrants for data in their "possession, custody, or control," regardless of whether that data is stored in the US or abroad.

For a SaaS provider based in the US (or with a US parent company) managing a cloud for a European or UAE client, the CLOUD Act creates a significant conflict of laws. If the provider holds the encryption keys, they have "control" over the data's legibility. European regulators, following the Schrems II decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), have expressed concern that this US government access is incompatible with the GDPR.

As a result, a DPA is not only a requirement for domestic compliance but is the primary mechanism for managing "Standard Contractual Clauses" (SCCs) and "Supplementary Measures". These clauses obligate the SaaS provider to:

Challenge government requests that are overbroad or conflict with foreign law.

Provide "Transparency Reports" to customers regarding the number of government requests received.

Implement end-to-end encryption or HYOK models where appropriate to ensure the provider cannot comply with a decryption request.

Without a DPA, the customer has no legal assurance that the SaaS provider will protect their data sovereignty against foreign government reach.

The Fifth Amendment and Compelled Decryption

An interesting federal legal nuance in the US involves the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. In some legal cases, courts have debated whether a person can be forced to provide an encryption passphrase.

Foregone Conclusion Exception: If the government can prove with "reasonable particularity" that a person knows the password and that the device contains the evidence they seek, the act of production may be considered a "foregone conclusion," and the Fifth Amendment might not apply.

SaaS Context: This legal protection generally applies to individuals, not corporations. A SaaS provider, as a corporate entity, cannot typically claim a Fifth Amendment privilege to refuse a valid warrant for data they control.

This reinforces the importance of the DPA for the SaaS provider. If the provider is served with a warrant, the DPA establishes the protocol for how they must handle that request—ideally by referring the government to the customer, unless prohibited by a "gag order".

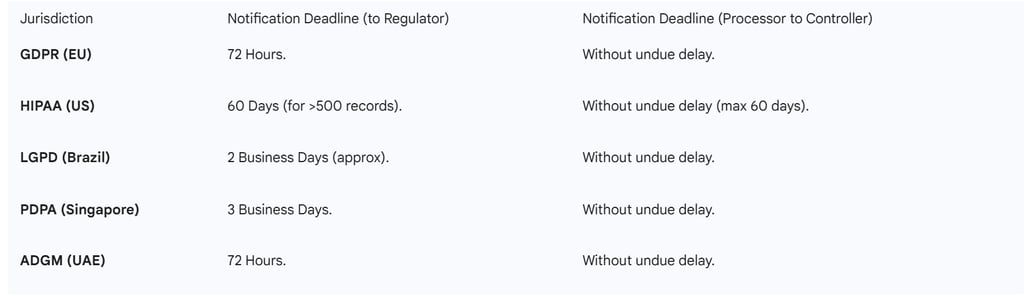

Breach Notification and the "Safe Harbor" Concept

Encryption provides a significant "safe harbor" under many laws, but this harbor is often contingent on the status of the encryption keys.

GDPR and "Risk to Rights"

Under Article 33 and 34 of the GDPR, a controller is not required to notify data subjects of a breach if the personal data was rendered unintelligible to any person who is not authorized to access it (e.g., via state-of-the-art encryption). However, if the SaaS provider holds the keys and the keys were also accessed during the breach, the data is no longer unintelligible. The "safe harbor" is lost.

Table 4: Breach Notification Timelines by Jurisdiction

A DPA is essential for aligning these timelines. For instance, if a SaaS provider handles data for customers in the EU and Singapore, their internal incident response plan must be tuned to the "without undue delay" standard, which the DPA will typically define as 24 to 48 hours.

The Role of Industry Standards and Certifications

While the law determines "status," industry standards like ISO 27001, SOC 2 Type II, and PCI DSS provide the framework for "how" a processor fulfills their duties.

SOC 2 (Trust Service Principles): Evaluates a SaaS provider on security, availability, processing integrity, confidentiality, and privacy.

PCI DSS: Mandatory for any SaaS handling credit card data, requiring strong encryption and key management.

ISO 27001: Provides a global standard for an Information Security Management System (ISMS), which often serves as the "technical and organizational measures" referenced in a DPA.

A DPA frequently includes an "Audit Right" clause, allowing the customer (or a third party) to verify the SaaS provider's compliance with these standards. Without a DPA, a SaaS provider has no contractual obligation to provide these audit reports or to maintain these certifications.

Conclusion: The Integrated Mandate for SaaS Compliance

The synthesis of global data protection regimes reveals a consistent principle: the classification of a SaaS provider as a "Data Processor" is driven by the act of "holding" or "maintaining" data on behalf of a customer, and this status is reinforced—not removed—by the provider's management of encryption keys. Across the GDPR, HIPAA, CCPA, LGPD, and the UAE’s federal and free-zone laws, a SaaS provider managing a third-party cloud is legally required to execute a Data Processing Addendum (or BAA).

The fact that the provider explicitly avoids accessing the data does not mitigate their status as a processor because they maintain the custodial responsibility for the data’s availability, integrity, and cryptographic isolation. In the eyes of the law, encryption is a security obligation, not a jurisdictional loophole. From a strategic perspective, the DPA is the foundational document that allows a SaaS provider to operate in the enterprise market, providing the transparency and accountability required for modern data governance. By implementing state-of-the-art encryption standards (such as AES-256 and TLS 1.3) and codifying these measures within a robust DPA, SaaS providers can effectively manage the "Cryptographic Key Paradox," ensuring they meet their legal duties while fostering the trust necessary for successful B2B product deployments in an increasingly regulated global landscape.

DPO Corner

Committed to build the trust.

Contact

Newsletter

+971(55)1600-798

© 2025. All rights reserved.

This platform